Lies the Canon Told Me: The Countless Jazz Classics Hiding in Plain Sight

How a chance encounter with an obscure 1971 Gene Ammons record made me think twice about what constitutes a classic

Greetings… If you’re new here, welcome! Thanks to everyone who checked out the Sonny Sharrock posts (in case you missed them, start here). I have more to say on that topic, which I hope I’ll find the time to share here at some point, but for today, here are some thoughts inspired by a chance used-LP purchase I made yesterday. This newsletter is still finding its level, in terms of type and frequency of content, but for now, I sincerely appreciate that you’ve chosen to spend a bit of time here at DFSBP. Please subscribe, share and stay tuned.

Yesterday, with some reluctance, I walked into my local record shop, Hudson Valley Vinyl in Beacon, New York. My hesitation had nothing to do with the shop itself — their selection is always impressive and their prices reasonable. Rather, it stemmed from my general wariness around accumulating more LPs. I have a healthy amount — let’s say: more than 600 and less than 1000 — and not remotely enough time to actually sit down and listen to them. So I try to keep a lid on it. But I found myself browsing, as one does, and one title caught my eye. After a quick iPhone snap of the back-cover personnel yielded a positive response from trusted pals in my most jazz-centric group text, I decided to spring for it. From past experience, I knew that there was at least some chance the record would get filed away without much more than a cursory listen, but with a $15 price tag, I felt OK with the gamble.

I dropped the needle soon after I got home, and what I’d envisioned as a quick sampling turned into a relatively rare full-LP spin. As I listened to the record and read up on it a bit, a couple things became clear:

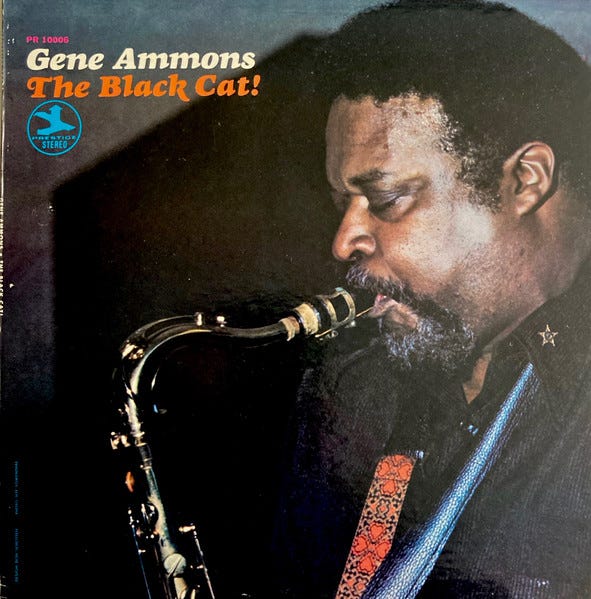

First, this album — a 1971 Gene Ammons date on Prestige called The Black Cat! (yes, the exclamation point is part of the title) — was obscure. I’m no encyclopedia, but I’ve been traveling in serious jazz circles for more than 25 years, and I’ve never heard a word about it. It’s not available on streaming, and according to Discogs, it hasn’t been re-pressed since the year after its release. (UPDATE: Thanks to several commenters for flagging my mistake just above — The Black Cat! actually is streaming as part of a 1997 reissue under the title The Legends of Acid Jazz.)

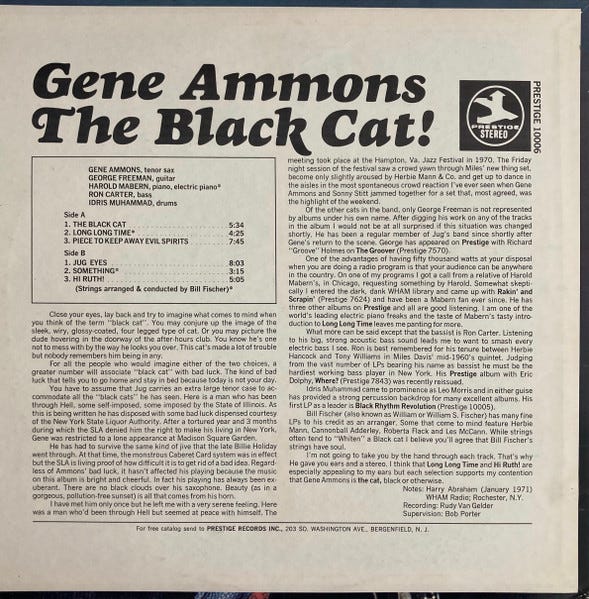

Second, it sounded incredible coming out of the speakers. I wasn’t necessarily surprised, as The Black Cat! initially drew me in based on its stellar lineup, highlighted by Harold Mabern on both acoustic and electric piano, Ron Carter on bass and, on drums, Idris Muhammad, a musician who’s become the shining star of the aforementioned text thread, his presence on a given session serving as a sort of embossed mark of superlative quality. Also on board, of course, was the leader on tenor, along with a guitarist, George Freeman, whose name rang only a vague bell. (See below for more on George.)

Considering the vintage and the personnel, I wasn’t sure if I’d be getting a funky rhythmic profile or something more swinging. As it turned out, a little of both was in store, along with some other flavors, across around 35 palatable and engaging minutes: a steady-rolling blues shuffle (the Freeman-penned title track); two string-accented pop covers, beautifully chill, backbeat-driven versions of “Long, Long Time,” the 1970 Linda Ronstadt tearjerker written by Gary White, and George Harrison’s immortal “Something”; two handsome midtempo swingers, “Piece to Keep Away Evil Spirits,” by the obscure Chicago saxophonist Gene Easton, and Ammons’ “Hi Ruth!”; and another original by the leader, the James Brown–esque “Jug Eyes.”

If the album sounds formulaic based on that description, it absolutely, 100 percent is. You could no doubt walk into dozens of other record shops across the country and turn up hundreds, if not thousands, of other jazz records of a similar vintage — let’s say 1968 through ’74 — and general profile: kind of straight-ahead, kind of funky, maybe with some strings thrown in here and there, very likely featuring Carter and/or Mabern and/or Muhammad. You may have flipped past one or 10 of these during your own weekend browsing.

But as I listened, soaking up the way Ammons’ masterfully gutsy blowing played off Freeman’s sometimes deep in the pocket and sometimes surprisingly abrasive (dare I say almost Sharrock-ian) lines on the title track, or how utterly classy the rhythm section sounded on “Evil Spirits,” laying out a red carpet for the leader to stroll on, or the buttery smooth blend of the leader’s breathy tenor, Mabern’s electric keys, Muhammad’s ultra-tasteful groove and the period-appropriate strings on “Long, Long Time,” I found myself attuned both to the album’s essential generic-ness and to how irrelevant that fact — perhaps a pejorative on paper — felt mid-spin. Context aside, the album simply worked.

It struck me as I listened that something about not just my own taste profile but about the larger conversation around jazz, critical and otherwise, had somehow conditioned me to ignore an album like The Black Cat!, to sort of wave it off as Just Another Jazz Record, the kind that the seasoned listener feels they can almost hear in their head without actually hearing it. (This feels like a good time to state for the record that I have never owned a Gene Ammons album before yesterday, a fact I’m almost ashamed to admit…) And this glossing has something to do with the privileging of obvious innovation in the way jazz is discussed. The essential albums, we’re taught, are the breakthroughs, the ones that established some new paradigm, or perhaps shattered an old one. And the ones of these that stand up to infinite listens become rightful classics, your Kinds of Blue, Shapes of Jazz to Come, Loves Supreme.

But, in the actual moment of listening, can we really say that any of the above canonical titles are better, so to speak, than a record like The Black Cat? As the Ammons LP spun yesterday, I could not have felt more fulfilled, nourished, by what I was hearing. As Harold, Ron and Idris laid down that lean, badass groove on “Jug Eyes,” for example, and Gene waded into his solo and started gradually turning up the heat, sustaining the intrigue at every step, I wanted for nothing. I did not wish for — as critical discourse can sometimes seem to implicitly encourage — the music to issue me some sort of challenge, to throw me a curveball, to destabilize me in some way in order to keep me interested. I did not think about how, by a certain metric, this music could have been viewed, even back in 1971, as behind the times, arriving as it did the same year as obvious game-changers like Jack Johnson or Journey in Satchidananda or The Inner Mounting Flame or even, say, a less overtly new but still obviously contemporary statement like Freddie Hubbard’s Straight Life. There was nothing signaling to me, in other words, that I was not, in fact, listening to a classic.

I think that without really realizing it, for a while I’ve been intuitively interrogating my own tastes along these lines. Whereas 10 or 15 years ago, when walking into a used record shop, I would have probably bee-lined for, say, the Anthony Braxton or Cecil Taylor section, overlooking the dozens of Black Cat–esque titles on offer, often in the $1 or $5 bins, these days I’m a lot more attentive to that enormous, largely un-canonized zone of straight-ahead-ish jazz from the ’70s and ’80s, out of step with larger trends and fashions but just unassumingly excellent. (Mind you, I’m still perusing those Braxton and Cecil bins! This is all an additive process, not one of successive phases…) There’s this beautiful fact about jazz where, when you flip a given record over, no matter how obscure, and see names like Mabern’s, Carter’s, Muhammad’s, you’re never going to go wrong — there’s a standard of excellence in the playing that is simply not going to dip. Sure, a given session may have a certain kind of juice — where the blend of tunes, the inspired-ness of the solos and/or the quality of the production all align to produce something truly extraordinary — but regardless, there’s always going to be some kind of satisfaction in hearing established masters at work.

And that’s a satisfaction that, currently, for me, carries more weight than some kind of canonical greatness. I find myself less interested in what the music signifies than simply how it feels coming out of the speakers. I’m not sure what the overriding takeaway is here, but what I mean to say is that, yesterday, The Black Cat! was my own personal Kind of Blue, my private Love Supreme. For those 35 minutes, it felt like all I could ever want to hear. And that experience reminded me that absolutes are boring, and that the outsize attention repeatedly bestowed on obvious masters and their acknowledged classics can obscure the wonder inherent in a more unassuming but no less crucial brand of genius. You never know when you’re going to find your next Black Cat, but next time you’re browsing the bins, you’d do well to keep an eye out.

*****

A few P.S. items here:

-George Freeman, the guitarist featured on The Black Cat!, is a fascinating figure. Brother of cult-favorite tenor great Von and Buzz/Bruz Freeman (a drummer I recognized from his work on the excellent early LPs by John Carter and Bobby Bradford’s collaborative band), and uncle to Chico, he’s been active since the early ’50s. He turns 97 next month and is still at it! There’s a nice Chicago Sun-Times piece on him here.

-Other writers have touched on some of the themes I’m getting at above:

Phil Freeman has written smartly about the tension between straight-ahead sounds and more avant-garde, critically acclaimed jazz in the 1970s both here and here, in the process referencing a book I haven’t read but would like to: Soul Jazz: Jazz in the Black Community, 1945-1975, by the prolific broadcaster and journalist Bob Porter, who also worked as a producer for Prestige and other labels. Among the hundreds of sessions he produced: The Black Cat! itself. (Porter died at age 80 in 2021; read Giovanni Russonello’s informative obit for more on his years of service to the jazz cause.)

Mark Stryker, an Ammons connoisseur, has memorably quipped, “I often say that there’s nothing wrong with jazz education that couldn’t be fixed by firebombing all the music schools with Gene Ammons records.” He elaborates in this fine interview with Ethan Iverson.

And Morgan Enos has frequently made a strong case for appreciating highly effective jazz as much as radically innovative jazz, such as in this rich tribute to Hank Mobley’s 1960 classic Soul Station.

I wrote once about Sonny Rollins Brass/Trio and a pedant of my acquaintance got all up my nose because it wasn't the greatest Sonny Rollins, in his opinion. This made me cross. I like something Wynton Marsalis said in a random interview on Australian TV. He was asked who the greatest jazz musicians were, and he said, "There are so many great people who on any given solo can manifest something you never thought of, and it's not reduced to just the people who are famous. It's like life." I think a canon in any field is useful for pointing you to some good work but it doesn't tell you useful things about the rest of the field.

Beautiful Hank!!!