A Tale of Two Sonnys, Part 1: Sonny Sharrock, Herbie Mann, "Wild Free Music" and More

Learning to love the weird duality of the early Sonny Sharrock discography

Greetings — if you’re new to this Substack, thanks very much for coming on board. As of now at least, as was the case with the old Dark Forces Swing blog, there’s no particular format or frequency to the newsletter. I’m simply using this as a space to delve into anything that interests me, and this time around, that’s the early discography of Sonny Sharrock.

There are currently three parts to this ongoing deep dive — the piece below, where I discuss the strange duality of the early Sonny canon, divided neatly between free-jazz sessions and something like their polar opposite, his extensive work alongside the funky flute player Herbie Mann. The second is a full rundown/unpacking of, more or less, every single officially released Sonny Sharrock session from 1966, when he debuted on record with Pharoah Sanders, through 1970, the tail end of a busy period of recording and live performance with Mann, after which he moved back to his hometown of Ossining, NY, and entered roughly a decade of semi-dormancy.

The third looks at how Sonny’s twin passions for terror and beauty played out in the later part of his career, via Last Exit and albums like Highlife and Ask the Ages.

Thanks so much for reading and if you enjoy what you read below and in Part 2 and Part 3, please share this post and subscribe to receive future dispatches.

“I joined the [Herbie Mann] band and ‘Girl From Ipanema’ and ‘Comin’ Home Baby’ were the tunes the band was doing. And I had come from playing some wild free music on the Lower East Side. … So like we would try to do a thing like ‘Summertime’ and I would take one of my solos and it would completely shatter the tune. That’s the way it was. And there was a lot of hate.”

—Sonny Sharrock, Down Beat interview, 1970

There are stages to Sonny Sharrock fandom. Maybe it’s Ask the Ages that pulls you in, with its searing riffs and avalanche of pure conviction, or Black Woman, with its torrent of cathartic feeling. Then perhaps it’s on to the brash chaos of Last Exit or the exquisite miniatures of Guitar. You fill in some of the gaps: the early Pharoah Sanders sessions, maybe Don Cherry’s Eternal Rhythm, the somewhat more obscure post-comeback sessions like Seize the Rainbow and Highlife, or the disco one-off Paradise. Whatever path you take, your explorations inevitably lead you to the period (from roughly 1967 through 1972) when Sonny was a member of the Herbie Mann band, and from there you have a choice.

For a while, my choice was, more or less, ignorance. Even as I developed an insatiable appetite for Sonny Sharrock’s sound, even as he became unquestionably my favorite guitarist and possibly my favorite musician, period, I mostly steered clear of his collaborations with Mann, the eclectic and pop-savvy jazz flutist.

In 2002, the year before his death, Herbie Mann hit the nail on the head, when it came to his perception among serious jazz heads: "To most jazz critics I was basically Kenny G. I was too successful. I made too much money.”

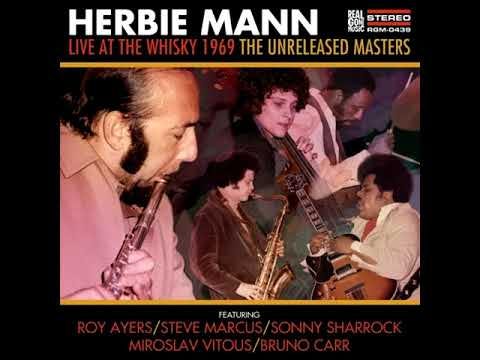

I have to admit that I too mostly wrote him off — too many years of seeing questionable album covers in dollar bins, I guess. At some point I learned that Sonny Sharrock had played with him extensively, a fact that certainly gave me pause. OK, wait… the godfather of noise guitar teaming up with the kingpin of funky flute? I know that at some point I picked up a used copy of Live at the Whisky a Go Go, fished around on Side 2 for the brief, anomalous Sonny solo. But that’s pretty much where I stopped.

A few years back, though, as I realized that my perennial Sharrock obsession wasn’t going anywhere, I started to feel unsettled by the incompleteness of my listening journey. I’d come across a Mann album like Windows Opened in a used record shop, see Sonny on the cover, and feel perturbed, almost ashamed that I’d never heard it. If this was going to be a lifelong thing, then I needed to go all the way — into the Mann hole (sorry…) and beyond.

So I started a Google Doc where I’d periodically log my spins of various Sharrock-era Mann albums, noting which tracks featured Sonny solos, amid many where he was either playing an anonymous background role or was even simply inaudible. (Until today, I didn’t realize that Thurston Moore had undertaken something similar and put together a kind of Sonny-with-Herbie supercut.) Along the way, I started filling in other gaps, the many obscure session credits that dot Sonny Sharrock’s career: the Brute Force LP, a couple of dates with his Mann bandmate Roy Ayers, later, mostly unsung appearances on albums by Pheeroan akLaff and the French guitarist F. Robert Lloyd. What I realized pretty quickly is that none of it was inessential.

We all have these realizations, which over time all boil down to the same thing: When it comes to any truly great artist, received wisdom about the highs and lows of their catalog is, after a certain point, B.S. What was keeping me away from Mann-era Sonny was, in the end, not that different from what had kept me away, for a time, from, say, ’80s Bob Dylan or Miles Davis, or Metallica’s Load and ReLoad. It seems like every time I just set aside the baggage regarding a certain undervalued or even outright maligned era of a given catalog and dig in, I find that what’s there is almost always, at the very least, interesting and very often revelatory.

Was Sonny Sharrock a fish out of water in the Mann band? Was he, in some sense, leaving his own tribe when he signed up with the commercially savvy flute player? Of course, and he often said so in interviews, as you can read above. He even spoke openly about tensions within the group. In the same Down Beat interview, he discussed a period when his then-wife and close musical collaborator Linda was traveling with the group and sitting in, performing material from Black Woman, Sonny’s now-legendary debut as a leader. Two priceless examples are heard on an extended batch of Mann & Co.’s 1969 Whisky recordings that came out to little fanfare in 2016.

As Sonny put it, “Herbie's group hated the music, they hated [‘Black Woman’], and they hated to play it. Well, Herbie had big enough ears to see that it was something there. But the rest of the group hated it and they would lay down every time we started playing.”

I’m curious to know exactly who the haters were in the band, because these Whisky renditions are excellent — Ayers, bassist Miroslav Vitouš and drummer Bruno Carr all sound extremely comfortable and effective in a churning free-jazz mode on “Black Woman,” while saxophonist Steve Marcus screams gamely alongside Linda on “Portrait of Linda in Three Colors, All Black.” Mann stays mostly out of the fray here, but let’s not forget: He’s the one who produced Black Woman and released it on his Atlantic subsidiary Embryo.

“I was with Herbie Mann at the time, and he started producing for Atlantic, and he said one night, ‘You need to make a record, so come on,’” Sonny told Ed Flynn in a 1993 on-air interview. “And that's how we did Black Woman.” (Note: The Flynn interview and many of the other sources cited here and in Part 2 of this piece are archived on an invaluable Sonny Sharrock tribute site formerly run by the late free-jazz champion — and, later, wife of Henry Grimes — Margaret Davis. This URL was the virtual counterpart to Sweet Butterfingers, a zine/booklet that Davis and the broadcaster Charles Blass self-released after Sonny’s death in 1994, compiling various interviews and articles.)

It’s hard to think of a more uncompromising musical statement than Black Woman, and it’s clear that whatever the differences were in their home-base aesthetics, that there was a mutual respect between the two men that transcended any outside tsk-tsk-ing about the incongruity of their pairing. Here’s Mann in a 1971 interview:

“… [Sonny’s] been with my band for three years. He’s still with me, because I like the way he plays guitar. Lots of people say they can’t understand how Sonny Sharrock can be in my band. The only reason for them saying that is: possibly they think that when you’re a bandleader you expect all your children to be brought up in your exact image. Which just shows that people and critics don’t know anything about individuals. People have assumed that they know me and my music because of the way I play— or their interpretation of how I play. But nobody has hit on it yet. They don’t know me.”

Yeah, Herbie!

Sharrock spoke about the collaboration in a 1973 interview with the great, still-active jazz writer Richard Scheinin, also archived on the Sweet Butterfingers site.

“I worked a lot of places with Herbie on big festivals, you know. … And it was really strange to be the only cat that plays the ‘new music’ and to be in those kind of situations, you know; like, to play the ‘new music’ and to go on before Ray Charles and after Roberta Flack is kind of strange, I think. … Well, Herbie never put musical restrictions on me: That's one thing I can say. He never said ‘Play this way’ or ‘Play that way.’ What usually happened was I would get one solo a night where he felt it fit the rest of the music, you know, because it was outside of what they were doing, so it would usually be on the big crowd-grabber of the night I would come out and do my thing, you know [laughs].”

Incidentally, Questlove’s brilliant Oscar-winning Summer of Soul doc contains an absolute ripper of a Sharrock crowd-grabber, filmed during a June 1969 performance with Mann at the Harlem Cultural Festival. Another great example of Sonny “shattering the tune” is here:

And here’s Mann again, from a late-’80s Musician interview with Ted Drozdowski, who later wrote an outstanding Sharrock career overview for Premier Guitar: "l thought of Sonny as my John Coltrane and l’d reached the point where I wanted to have some contrast in the band. … The reaction was often hate, total hate."

So there was a fairly staunch form of advocacy going on here, especially given Sharrock’s open disavowal of the traditional role a guitarist would reasonably be expected to play in a band like Mann’s (or, let’s be honest, almost any other band on the planet at that time). Here’s Sonny from a 1970 Melody Maker interview:

"I don’t like to comp — I hate it. I don't know any chord sequences, or any tunes either. You name a tune, and I don't know it! It's a very personal technique. I couldn't write a book about [my technique], or How to Get a Gig With Herbie Mann … it's just some home-made stuff that worked out.”

And at this stage, Sonny was already volunteering the anti-guitar stump speech that he’d continue to put forth in numerous later interviews. “I hate the guitar, man,” he said in the Melody Maker interview. “I wanted to play saxophone but I have asthma so I bought a guitar.”

Sharrock clearly realized how beneficial the Mann affiliation was, both financially and creatively — not just a steady gig during a time when he needed it, but a chance to be himself, albeit in relatively small doses.

In the Scheinin interview, he talks about how the initial invitation from Mann arrived when he and Linda were “living on East 3rd Street doing very bad [laughs], and we didn't have a phone, our phone had been lifted, and we were just waiting, you know for whatever.”

In a 1990 Motorbooty interview, Mike Rubin — also still producing great work, like this revelatory recent profile of Linda Sharrock — asked Sonny about the Mann years.

What do you think of the stuff you did with Herbie Mann now? I’ve never heard it, but a friend described him once as just this sort of lightweight, whitebread flute player.

No, Herbie gets rapped for that, and I don't know if that’s quite fair. Herbie’s a good player, and he’s one of the best bandleaders in the business. Seriously. He’s a good cat. He’s got real big musical ears. He can hear a lot of things that a lot of people can’t hear. Like, he kept me in that band against the objections of all of the really big people and musicians who were telling him to get rid of me. I do believe that Herbie lost some gigs because I was in the band.

He went on:

“The first time I played London with Herbie, we did this festival. Sarah Vaughan, Thelonious Monk’s band, and Herbie Mann. … And at that gig, people in the audience were shouting, ‘Get him off! No! No!’ In Switzerland, the first time I played at the Montreux festival, a man stormed the stage and went banging on the stage, ‘This is not jazz! This is not jazz!’ You gotta realize that there wasn’t even a rock press back then. There was no such thing as an alternative anything, there was just the mainstream of jazz. Coltrane was being lambasted all over jazz for doing what he was doing, and the younger cats like myself were catching hell too. And there I was, in the midst of pop-jazz with Herbie Mann, “Memphis Underground,” and I’m doing all this crazy shit. So that really took a lot of heart for Herbie to keep me on the band through that.”

It’s important to note here that the association had a mutually legitimizing effect — after all, I doubt I (or Thurston Moore, for that matter!) ever would have thought to take a deep dive into the late ‘60s and early ‘70s Herbie Mann catalog if he hadn’t hired Sonny. Herbie gave Sonny a stable platform and a degree of immunity from outside criticism of his radical style; in turn, Sonny gave Herbie some true fire — and, it must be said, a strong element of vanguard Black expression in a group led by a white instrumentalist who wasn’t exactly known for pushing the envelope. (It seems that everyone at the time, Black or white, was looking for a taste of that vanguard — Mann’s “I though of Sonny as my Coltrane” quote above reminds me a bit of James Brown urging saxophonist Robert McCollough to “Blow me some Trane, brother!” during his white-hot solo in “Super Bad.”)

And maybe that fire actually changed the makeup of Mann’s audience. In a 1990 interview with Ben Ratliff, one of two essential Sonny interviews by Ratliff conducted on-air at WKCR and archived on the Sweet Butterfingers site, he had this to say of the Mann experience:

“When I joined Herbie Mann’s band, he was coming off of hits like ‘Comin’ Home, Baby,’ and he was also right in the middle of his bossa-nova period, so people who went to jazz clubs looked pretty much like those people you see on television, you know, I mean they were pretty much straight George Bush Republicans, you know, that went to see Herbie, at any rate they didn't come down to Slug’s, but you know, they did come down to the Village Gate and to other places I played with Herbie. So I would upset a lot of those people. But then later on, after ‘Memphis Underground,’ Herbie started to get more kids in his audience, and I found more acceptance.”

Roughly 50 years on from the Mann-Sharrock collaboration, it’s a thrill to have not just early examples of Sonny Sharrock presenting his “home-made stuff” (marked by an effect that he would later call, in the Motorbooty interview, “the buzzsaw, the rip” — for more on that, see the footnote following this post) in a completely sympathetic environment, i.e., “playing some wild free music on the Lower East Side” — as on, say, Pharoah Sanders’ Tauhid, Marzette Watts’ Marzette & Company or Black Woman itself— but also to hear him swimming against the current, airing his aggressively outré style in a thoroughly conventional context.

He spoke about the odd blend of personalities in the Mann band in the 1970 Down Beat interview:

That’s a strange band, man.

It’s five different bands, man. It all depends on who’s soloing. That’s good in a way, but sometimes it gets kinda weird. You know, sometimes the direction just gets lost completely. Nobody knows what you’re gonna do. It’s weird for me, man — I don’t know about the other cats — because for two years, I’ve been playing against things.

He goes on to assert his need to move on to his own bandleading ventures, in the vein of the then-just-released Black Woman. As we now know, these would be somewhat frustratingly scarce, at least until his resurgence in the ’80s, when Bill Laswell took on the role of championing Sonny and clearing a path for him. But if the Herbie Mann years were sometimes “kinda weird” — or even downright tumultuous; in his 1989 WKCR interview with Ben Ratliff, Sonny says of his Mann tenure that “I'd get fired a lot and come back” — is there anyone with any kind of creative imperative who hasn’t experienced this, i.e., entering into an unnatural or ill-fitting arrangement in the interest of making a living?

And moreover, however out of place Sonny’s “one solo a night” may have seemed, however much “total hate” it incited from audiences, that moment was fully his, backed by the imprimatur of a popular, established bandleader who trusted Sharrock’s musical voice completely and clearly valued it precisely for its fly-in-the-ointment qualities. As far as keeping-the-lights-on gigs go, Sonny Sharrock could have done a lot worse. And as listeners, now, so can we.

***

As a footnote here, and as a lead-in to Part 2, I want to quote in full this remarkable passage from aforementioned Motorbooty interview, where Sonny describes the genesis of the abrasive trilling that became one of his most indelible sonic gestures.

At what point did you come upon the sound that you have?

The buzzsaw, the rip… It was a combination of things. I was very much in love with Albert Ayler’s sound, with Pharoah’s sound, when Pharoah would do that high intensity sound, and of course with the playing of Coltrane and the melodicism of Miles. All of these things were affecting me, and there I was right in he midst of it. Now, I like to play along with records, it’s a cheap way to play with very good bands. So one day I was playing along with this Miles record. Miles in Europe, and there’s a version of ‘Milestones’ on there that’s extremely fast, and I’m playing along with it, and at that point I could play and make it for about 16 bars, and then it would start to fade, but I found that if I did a trill on one string, I was able to reach certain things, and then the sound developed out of that trill. That’s when I started working on that, playing a repeated note very fast, like a buzzsaw, and to overpick the string. The lighter you pick, the faster you can go, but I pick very heavy. Try and make that fast, and you’ll get a sound of pulling the string. You’ll get two or three notes out of the one string at a time, because it’s something about it slapping back or something that gives you more notes and you get these overtones, and it creates a harmonic that’s kind of abrasive. It’s an abrasive harmonic which is a strange concept in itself. I guess that’s what it is. Some scientist will figure that shit out when I’m dead, but for now that’s where we’ll leave it.

So that’s what happened. I heard it, and I said, that is the sound that Pharoah, and Coltrane when he’s playing his harmonics, and Albert, that’s the sound they’re all getting, and that is the sound I want. That’s why I think I’m a tenor player. I’m a real sick motherfucker about that, man. I really do think I’m a tenor player. I’ve never been very much in love with the guitar. There are guitarists that I really like, and I like all kinds of guitar, but I don’t want to play like that. I hear something else. I hear tenor. I hear Albert. I hear Archie Shepp. I hear Bird. I hear Coltrane. There’s something else that they do. There’s another kind of sound in a saxophone.

The clip you posted of "shattering the tune": It's funny, I can hear how Sharrock's solo is "out," but it's also so within the lines, it's totally immersed in jazz language, blues language.

Beautiful, informative, passionate, honest. Bravo Hank!